How Many Patients My Father Saved is Unknowable—But Why They Were Saved is Undeniable

Dr. Jack Kamen passed away this week—leaving the world a profound lesson of the role of freedom of innovation in medicine.

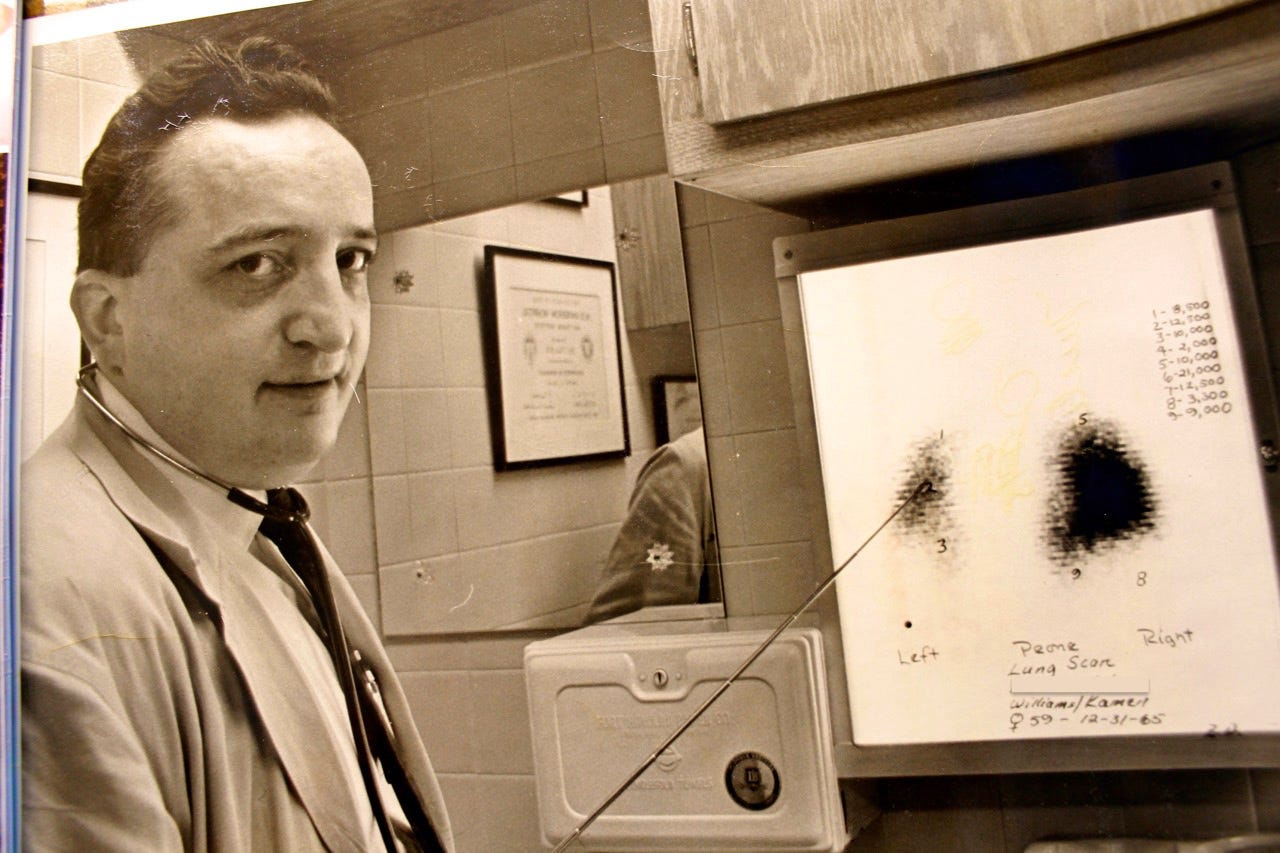

My father, Dr. Jack Kamen, passed away this week from respiratory failure due to COVID-19. Just three-weeks shy of his 97th birthday, Dad had been suffering from several other ailments and the vagaries of old age for quite some time when COVID came and ended his life in a matter of days. Yet, that he succumbed to respiratory failure after a luminous medical career during which he saved hundreds of thousands from suffering a similar fate stings bitterly.

Still, the story you are about to read about the way my father practiced medicine is one that conveys a cautionary tale that the world—still seized by the scourge of COVID—must heed.

My father practiced medicine by focusing solely on the one issue that was always of greatest importance: The patient who was before him. As he assessed each individual patient, he was not thinking about a previous patient, or the ones that would follow. He was exclusively engaged with the patient in front of him. And he would devise a plan of care and treatment ideally suited to that patient—and that patient alone—based upon his knowledge, experience and clinical expertise.

He was a doctor being a doctor.

So it was when a man who had been in a bad car accident came to the emergency room at St. Mary Mercy Medical Center in Gary, Indiana in the late 1960s. Dad, who opened Indiana’s first intensive care unit there a few years before, assessed “Manny” (not his real name.) In the book I co-wrote with my father about his early days as a physician, Dad noted:

“X-rays showed Manny had numerous rib fractures and multiple lung hemorrhages. This internal bleeding caused the normally spongy lungs to become sodden and heavy. Breathing was labored as Manny tried to breathe with a chest that had multiple rib fractures.

His respiratory distress worsened upon arrival in the trauma room. He was rapidly intubated— a plastic tube inserted through the mouth into the trachea (windpipe) — and placed on a respirator which did his breathing for him. The tracheostomy followed. Manny was in the unit for one week on a respirator when an insidious but ominous change occurred. Small traces of blood began to appear in the tracheotomy tube. It was called to my attention by the Chief of Respiratory Therapy who noticed it when an ICU nurse was suctioning secretions from the opening.”

Dad went on to explain.

“Patients undergoing any major surgery will almost always have a plastic tube inserted into their trachea with the protruding end attached to an anesthesia apparatus. The anesthesiologist or the nurse anesthetist would then be able to "breathe" for the patient by either squeezing on a breathing bag or turning on a respirator. Patients who are in respiratory difficulty, such as Manny, have these tubes inserted as lifesaving measures as soon as possible. In order to make this system airtight, so the oxygen or air will go into the lungs and not escape around the tube and out of the mouth, a seal between the tube and the tracheal wall is needed. This is provided by inflating an inflatable cuff that surrounds the tube near its tracheal tip. This ring, or cuff, is inflated through a smaller tube of its own with small increments of air, until the system is tight. But herein lies the problem.

Although care is usually taken in expanding the cuff, the actual pressure which the cuff exerts against the delicate airway tissues is difficult to measure, and at times, the force may be excessive. Combined with malnutrition, common in the acutely ill or injured, and long-term placement, (days, weeks, or months instead of hours as in surgery), the airway membrane may become ulcerated or eroded. If erosion continues, the trachea may perforate, either into the esophagus (gullet) which is directly behind it, or into a large artery—two events which carry a fatal prognosis. Many devices and cuff modifications had appeared, but none proved to be sufficiently successful in reducing the incidence of tracheal erosion. On hearing the news of Manny's worsening condition, I inspected the suction matter and confirmed that blood was indeed being brought up—the first sign of erosion.”

Manny—the patient laying in the ICU bed—was the only patient in the world in that moment for my father. Dad knew Manny was in grave danger, and Dad needed to find a swift solution if Manny was going to survive. It was the ICU nurse’s placement of a piece of foam under Manny meant to ease his bedsores that gave Dad a far-fetched idea. He went for it.

In a flash, Dad left the ICU and raced down to the hospital’s Central Supply to get a new tracheostomy tube. He ripped off the air cuff. Then he got an old seat cushion and the hospital’s maintenance department punched out a cylinder of the foam rubber from the cushion. Dad put a hole in its center and fitted it on the tube where the air cuff had been. Then he cut off the thumb of a surgical glove and made a covering for the foam which he then glued to the tube. Then he flew back upstairs to Manny’s bedside. The foam rubber on the makeshift tube was allowed to re-expand by allowing the air to go in. Manny was reconnected to the respirator.

Dad writes:

“Then we waited. The respirator went through three cycles and we all relaxed. ‘It works! It works!’ from an ICU nurse. ‘It's airtight and it works!!’ And work it did. The bleeding stopped and in three weeks, Manny was able to breathe on his own. The tube was then removed and a week later, he was discharged from the hospital...ready to go back to work.”

When we were writing the book together, Dad and I spoke about the “moral question” of what he had done…using an untested, makeshift device experimentally in dire circumstances, such as Manny’s. But Dad was emphatic and resolute: What he had done as Manny’s physician was, he said, an ethically acceptable practice. Dad explained to me that his only objective was saving Manny, and so he did what doctors are supposed to do: Bring all of their knowledge and expertise forward to save human lives.

The efficiency of his makeshift endotracheal tube even astounded Dad. He knew he had to share what had happened in his tiny ICU in Gary, Indiana with other physicians and researchers. How many other patients around the world could be helped or saved by such a device? The answer boggled his mind. Millions, perhaps. But where to start?

Manufacturing the new tracheal cuff on a general scale required research and clinical trials to accomplish. Dad contacted his colleague, Dr. Carolyn Wilkinson of Wesley Hospital in Chicago —now Northwestern University Hospital— where Dad was a staff anesthesiologist. As a physician who was frustrated by the problems using the standard tracheal cuff, Dr. Wilkinson was excited and positive about Dad’s “breakthrough.” Her faith in the new device was perhaps even greater than my father’s. Their investigative work began immediately.

Prototypes were made and tested. Finding the perfect kind of foam and sheathing for the new device proved to be difficult—but ultimately surmountable—tasks. Testing began…and the tube indeed became the game-changer it had been for Manny.

Finally, in the early 1970s, the Kamen-Wilkinson Fome-Cuf Endotracheal Tube was patented and brought to market by the Bivona Company. The device instantly revolutionized anesthesia and the care of patients around the world requiring long-term intubation. Variations of Dad’s original tube are still in use today worldwide.

This all transpired because Dad was a doctor being a doctor—and allowed to be so. By saving Manny in the manner in which he did, Dad was also saving millions more to come. He was not disciplined or fired by his hospital—rather, he was celebrated. He was not censored—and news of his colossal contribution to medicine was not suppressed. Instead, praise for this new-fangled device poured in from near and far. He was not described as a “fringe” doctor in newspaper reports because he dared to rely upon his own clinical expertise, research and knowledge to find a solution to a pervasive, potentially life-threatening condition that could occur hundreds of thousands if not millions of times to patients around the world. His medical license was not threatened. He was not called a “quack” on radio talk shows. He was not slapped with “far-right extremist” or “leftist-loser” labels for saving lives through clinical innovation.

In 2022, as the reputations of many brilliant physicians, researchers and scientists are savagely bludgeoned by major media, public health officials and licensing boards for putting forth cutting-edge, scientifically proven therapies for COVID-19, the world continues to battle a foe that—if not for the greedy vilification of these therapies—might have otherwise been conquered months and months ago.

Dad, yours was a life of brilliance, creativity, profound meaning and deep love for all humanity. You were perfectly suited to your chosen profession. The frequently “unorthodox” methods you were known to employ throughout your career to either save your patients or provide them with the highest quality of life possible were all acts of sincere compassion from one human being to another. Oh Dad, the lives you saved and made better.

As our family mourns the loss of our father, Dr. Jack Kamen, my most fervent wish is this: Let those who have risen to condemn doctors who are just trying to save lives in the ways they believe are best for their patients learn from Dad’s example. Let doctors see the patient that is before them, and treat each one as they deem appropriate for THEM. Please…no judgement, no derision—just wishes that patients, cared for by providers who know them and who are free to treat them in their best interest, return once more in health and joy to their loved ones.

#LetDoctorsBeDoctors

The fruits of labor saves mankind. Censorship destroys innovation. Doctors must be allowed once again to be doctors without reprisal.

Very touching and soo true. Lives are being and have been lost due to greed and an unconstitutional narrative.